Practice Advancement

The Ohio State University College of Pharmacy is committed to advocating for evidence-based policies and practices that improve patient outcomes and expand health care access. One of the current issues we are working on is expanding seniors’ access to services provided by pharmacists through legislation introduced in Congress. Below is an overview of this issue and where it will make an impact across the country.

Congress could expand access to essential services provided by pharmacists

The role of the pharmacist has evolved in recent decades to better align the care they provide with their extensive education and training, including receiving a Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) degree. State legislatures and boards of pharmacy, which oversee pharmacists’ scope of practice, have updated how pharmacists can practice to better support how they deliver care. However, many health plans don’t cover the services pharmacists provide, which stands as a barrier to patients to receiving needed care from their pharmacist. The Equitable Community Access to Pharmacists Services (ECAPS) Act (H.R. 1770 / S. 2477), currently introduced in Congress, aims to address this barrier by covering certain pharmacists’ services for Medicare beneficiaries. It is important to note these services will be covered by Medicare only if pharmacists are allowed to provide those services based on their state scope of practice.

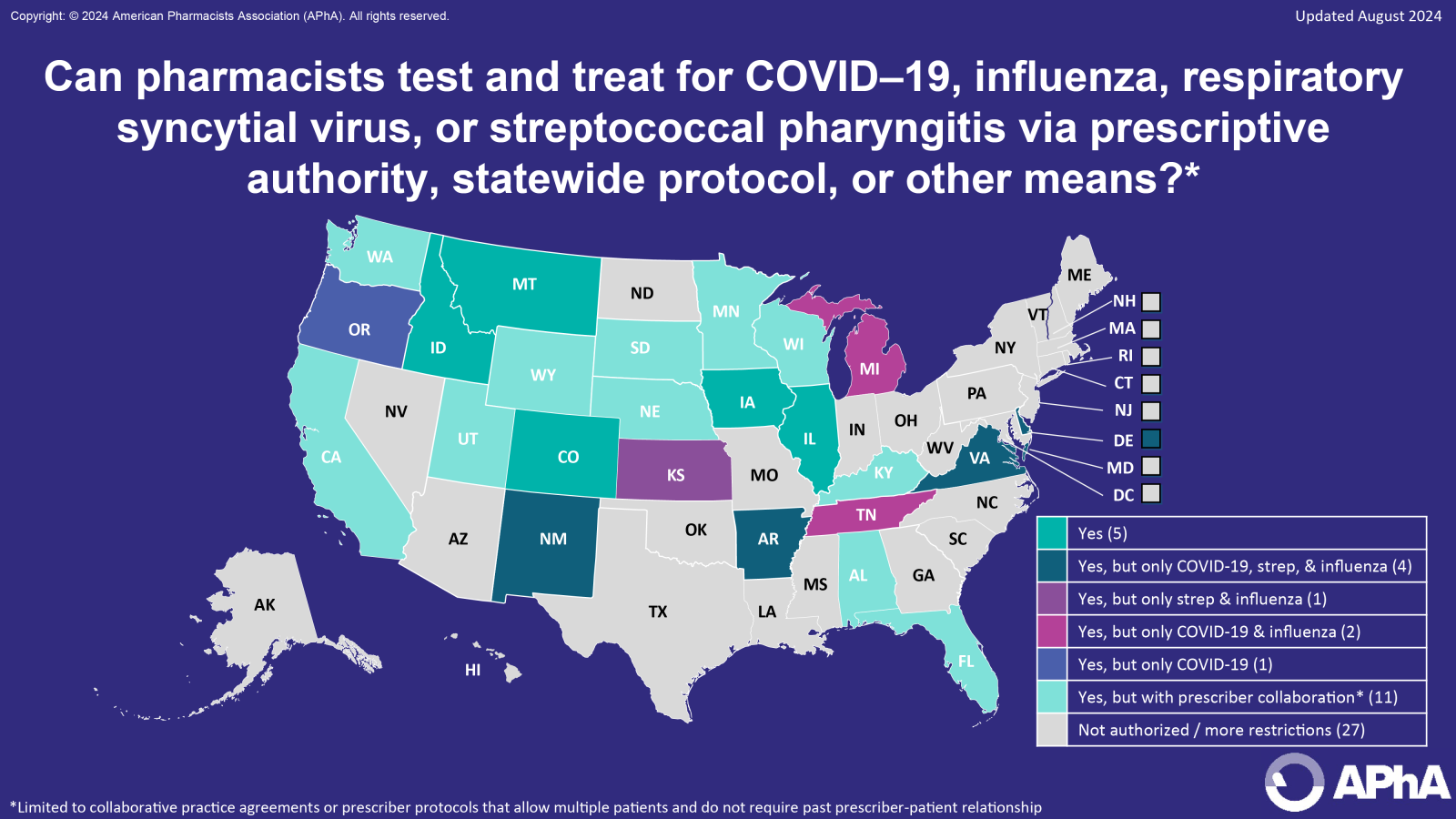

In addition to covering certain immunization services, ECAPS would cover services for pharmacists to test and treat for COVID-19, influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), or streptococcal pharyngitis, if allowed by their state scope of practice. To better understand the impact ECAPS would have if passed it is important to review pharmacists’ state scope of practice since it varies so significantly from state to state.

How pharmacists prescribe based on state scope of practice

Pharmacists’ authority is variable from state to state and falls on a spectrum of how independently they may prescribe. In 20 out of 24 states where ECAPS services are included in the pharmacists’ state scope of practice, pharmacists are required to provide services through collaborative practice agreements (CPAs), statewide protocols (SWPs), and standing orders (SOs).

CPAs are voluntary agreements where the prescriber delegates certain functions to the pharmacist, which often include initiating, modifying, and discontinuing therapy as well as ordering and interpreting laboratory tests, according to the terms of the agreement.

SWPs and SOs are distinct from one another. “A [statewide] protocol is the plan or process for carrying out a certain activity.” For example, the process of evaluating a patient, furnishing a medication to the patient, documenting activity, and informing the patient’s primary care provider. “A standing order is an order or directive for a specific action.” For example, a prescriptive order to furnish a specific medication that “is not limited to one particular patient.” Protocols and standing orders can both fall on a spectrum of how restrictive they can be. For example, both protocols and standing orders can be more restrictive, such as being prescriber-specific, or can be less restrictive.

CPAs, SWPs, and SOs generally include explicit educational and training prerequisites, step-by-step instructions that cannot be deviated from, and requirements when a referral must be made to a health care professional other than a pharmacist, such as a physician. Instructions generally include what laboratory tests may be performed, and specific medications that may be prescribed if certain criteria are met by the patient and the pharmacist. Requirements also exist for communicating this information to a patient’s primary care provider.

In four out of 24 states where ECAPS services are included in the pharmacists’ state scope of practice, pharmacists can prescribe treatment without a CPA, SWP, or SO. However, pharmacists must still meet statutory requirements when providing ECAPS services. These requirements may include only prescribing drugs that do not require a new diagnosis or are minor and generally self-limiting, are diagnosed by or for which clinical decisions are made using a test that is waived under the federal clinical laboratory improvement amendments of 1988 (e.g, pharmacies must have a CLIA-waiver), or are patient emergencies.

Where will ECAPS have the greatest impact?

At the time of writing, the passage of ECAPS will have the greatest effect on 24 states where pharmacists’ state scope of practice includes relevant test and treat services. Across these states, pharmacists’ authority to prescribe is commonly through CPAs, however, in many states pharmacists can also leverage SWPs and SOs to expand access to these important medications. SWPs and SOs may vary in specific indication that pharmacists can test and treat for from state to state. For example, pharmacists in Virginia can test and treat for COVID-19, influenza, and streptococcal pharyngitis, and in Oregon, pharmacists can test and treat only for COVID-19.

In other states, test and treat services for COVID-19, influenza, RSV, or streptococcal pharyngitis are either not included in pharmacists’ state scope of practice or there are more restrictions that limit the ability for pharmacists to implement such services.

What are the next steps for ECAPS?

ECAPS stands to significantly address a barrier to patients receiving needed care from their pharmacist by providing a pathway to payment for providing this care to patients, without having any nationwide effect on pharmacist scope of practice. The 118th Congress adjourns on January 3, 2025, and lawmakers and advocates have until then to advance the legislation. For many patients across the country that don’t have access to the healthcare they need, Congress must consider ECAPS as a solution to leverage the pharmacist as an additional option for patients to receive critical care.